3/4 November 2014

‘EKSTRA’: SIMPLY SPECIAL, SIMPLY BEAUTIFUL

A film review by JC Nigado |

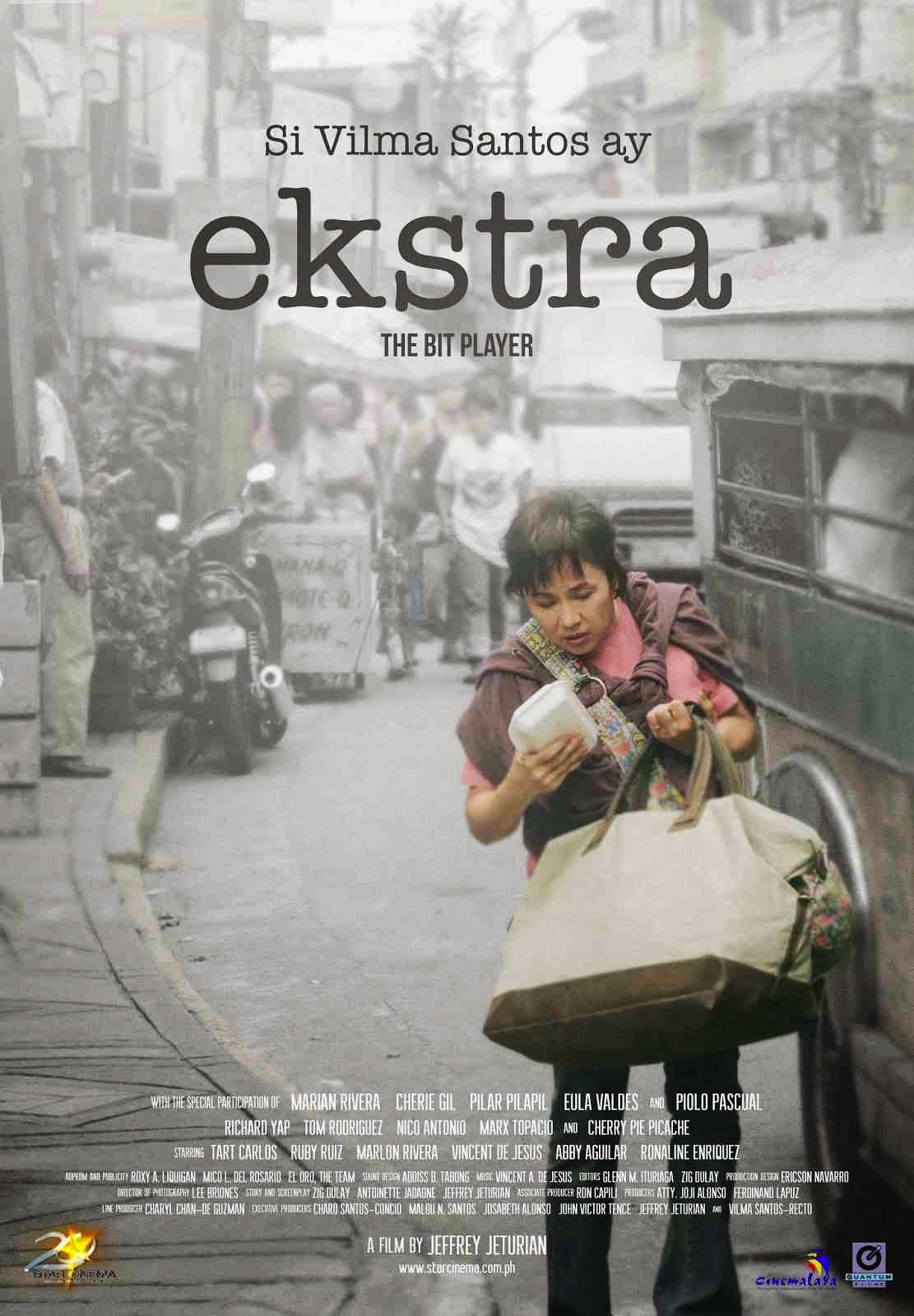

| Movie poster at Cinemalaya 2013 |

In his latest film, Ekstra, one of the two best films of 2013 (the other is Lav Diaz’s Norte: Hangganan ng Kasaysayan), Jeturian has further distilled his “minimalist” approach to its basic essentials, making his work look simple and yet, simply special and beautiful. The Cinemalaya blurb was accurate when it described Jeturian’s entry as a “socio-realist” film, but, unfortunately, only a few seemed to have pursued the film’s course and defined its broad and deep meaning.

Ekstra is David waiting to be discovered again. It is apparently small and easy enough to be viewed in one comfortable sitting, but big enough to encompass a sense of life as struggle of survival. To date, the first Vilma Santos so-called indie has reportedly grossed close to 40-million pesos, probably the first of its kind in this day of digital movies. It’s no mean feat, but small wonder, because the film features the biggest and most enduring star-actress in the history of Philippine show business.

At any rate, mentioning Diaz here is deliberate because his Norte runs along parallel lines with Ekstra, especially in their characters’ naked guts and will to survive. Besides, both Ekstra and Norte lend themselves well to interpretation and different readings, as the two films are translated from their respective literary sources.

If anything, Fyodor Dostoevsky’s Crime and Punishment (1866) is widely acknowledged as the basis for Diaz’s Norte. However, that’s acknowledging only half the story or half the film (Sid Lucero’s main protagonist); the other equally important half (Archie Alemania’s other principal character) is inspired by another Russian classic, a contemporary novel, in Alexander Sotzhenitsyn’s One Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovich (1963). Both Denisovich and Alemania’s character in Norte are unjustly incarcerated, and, while inside, they acquire an inner dignity as they find some meaning out of their desperate and degrading existence, transcending their environment with an intense spiritual awareness, despite the growing dehumanization of prisoners.

Like Solzhenitsyn’s One Day, Ekstra, unbeknownst to its writers (Zig Dulay, Antoinette Jadaone and Jeturian), is also rooted in the similar literary tradition of real-time narrative that happens in a day. Ekstra’s Loida Malabanan (judiciously portrayed by a plumpish Vilma Santos with striking sensitivity) hews closely to the character Guinevere Pettigrew in Winifred Watson’s 1938 novel, Miss Pettigrew Lives for a Day, an almost forgotten enchanting tale that unfolds over the 24 hours in the life of a neglected spinster.

Malabanan and Pettigrew belong to the underclass, the underprivileged that are often irregularly employed or out of work. Theirs are the stories of people who cope in the little ways they know how, keeping occupied with the mundane and absurd details of daily life, as they eke out a living, to make ends meet. Despite provenance and distant time, the novel and the film mirror each other, as they remind us that it is never too late to have a second chance, and that there’s always hope to go on living.

There are other literary gems, which are also set in one day, and each uses and follows the same time-span to explore the vagaries and temporality of life, or lives as the case may be. Like Ekstra, these novels deal with the tensions of everyday economics and practical philosophies that engage the otherwise ordinary people. There are no grand schemes and evils here, only simple pathos and the careless indignities of everyday life – sans frills, fusses or any gimmicks.

Anyway, Jeturian and his co-writers may not be aware that they have touched common ground with the works of certain literary greats, and their film “adaptation” posing as “original screenplay,” as it navigates life from dawn to dusk to dawn. Among the select, are James Joyce’s Ulysses (1922), Virginia Woolf’s The Waves (1931) and Saul Bellow’s Seize the Day (1952) – all presaging Ekstra by, pun unintended, a long shot. Still, Jeturian’s film neatly, if humbly, reflects the said novels’ eloquent textual and textural one-day structure and plot development.

Memory always serves well those who remember the exquisite relatedness of the various and diverse arts, especially the closeness and incestuous relationship of literature and film. With such an illustrious “kin” for background, Ekstra can’t afford to remain the “poor relation” that it is perceived to be. Alas, the enclosed social world of Jane Austen’s Pride and Prejudice of the early 19th century persists to this day and has transmogrified into a social bubble inhabited by cabal critics and bigots.

But the fact that the movie is set mainly in tabloid TV, what with its dumbing soap-opera mindset and sensationalist mentality, somehow elevates Jeturian’s filmic discourse to the level of postmodernist culture and socio-economic politics.

The film’s pervading theme of hope and survival is rendered powerless in a laissez-faire economy where commercial and fierce private interests rule. Jeturian deftly demonstrates the doctrine of individualism as personified by his sole principal protagonist, an everyday Filipino and a single parent, who faces the world and raises her collegiate daughter alone. Maybe, it’s on purpose that there’s hardly any mention of an absent husband or father throughout the film – it is not clear whether Malabanan was abandoned, separated, or the one who left her man in the movie. In addition, it translates well into the bigger picture that presupposes the absence of an authority figure that works for, and with, his people in a public trust. The true somebody who is looked up to and can be depended upon, in times good and bad.

In a country with no one man or woman enough to lead it to people’s right progress and development, Ekstra fits the bill, as it were, tagging one and all the price we have to pay for bad government and public indifference. Even God is silent, the film takes it for granted, and does not interfere in human affairs. Here, Big Brother brooks the form of an unseen force in the globalization enterprise of unrestricted corporate interests, where big business on a binge everywhere are buying and consuming us, as they practically take over and run our lives.

|

| Nationwide release poster |

Vilma Santos’s Loida Malabanan embodies the common Filipino worker, the overworked but underpaid all-around laborer who assumes various roles at multi-tasking. She then grabs every opportunity that is presented to her, unmindful of the required ability, skill or the appropriate equipment for the task, in order to earn more money for the long hours of toil, with no overtime pay. As such, Malabanan represents the majority of Filipinos who live in slum conditions, virtually imprisoned in abject poverty from womb to tomb, as they say.

It is to Jeturian’s credit that, expectedly or unexpectedly, he refuses not to treat poverty as pornography. His “cinematic” slum area is not the usual squalid squatter colony that shows curios or “exotic” destinations before the world.

Instead, he explores the microcosm of society (symbolized by TV) that has been reduced to mindless entertainment, as he exposes the systemic disease and disrepair of the general establishment (represented by the oppressive system and debauched working conditions).

The film brilliantly ends at the same place, where it began, signifying a continuing daily cycle of quiet, bittersweet surrender that, unlike Ivan Denisovich’s single day in a decade’s prison term, could even last Loida Malabanan’s lifetime. Under the circumstances, redemption, or what passes for it, comes by embracing fate with profound resignation.

Be that as it may, the ultimate defining scene where Santos, sensible and knowing, calmly gazes at the busy TV screen says it all: another day begins in repeat, as the world of corrupt culture and grasping politics turns.

JULIO CINCO NIGADO

Tagurabong City, Philippines, 2014